Andrew Moseley

Chorister 1930s

Memories of Life as a Cathedral Chorister in the 1930s

Thomas Armstrong's choir, photographed sometime while he was organist, 1928-1933. Andrew may be one of the choristers, but this would certainly have been the type of choir when he was a chorister: 20 installed choristers; 6 probationers (not in the photo); 12 adults (6 lay vicars and 6 'Sunday Men').

The steps to the School House, with the Head, Rev. Richard Langhorne (The Guv) standing at the bottom (photo from the Gibb Archive).

The old choristers’ school was a bleak stone building with three stories and a cellar, in which the maids and cook worked, lived and slept. The twenty choristers and six probationers had four virtually unheated dormitories, a lavatory and a double bathroom, in which the prefects had to supervise everyone’s total immersion in cold water each morning. One hot bath a week was permitted.

Downstairs, immediately behind the imposing front hall and door was R.W.B Langhorne’s (Guv’s) book-lined study from which he ran the school’s affairs and dispensed justice. Black marks were awarded for various offences, even for a failure in the weekly Latin verb test. Three such crimes incurred three strokes of a reversed clothes brush on the backside.

To the north of the hall was a full-sized billiard room and table, and beyond this a large common room, in which it was possible to read, or more likely, gamble in various games, using cigarette cards as currency. The seniors had a separate common room in which there was an antique radio, and another small room was equipped with a piano for lessons and practice.

The school playground with the steps at the far end, leading up to The Singing School (photo from the Gibb Archive).

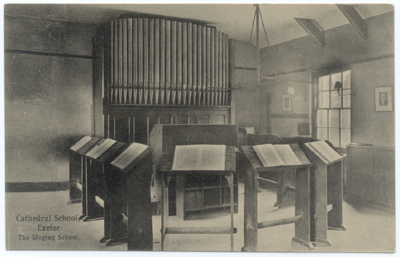

Inside The Singing School (photo from the Gibb Archive).

A further building to the north had a choir school above, fed by an outside staircase, equipped with a hand-pumped organ, a piano, music stands and cupboards housing sheet music and manuscripts – some hefty books referred to as “big A’s”. A prefabricated building housed two classrooms for juniors and seniors, which could be linked by sliding doors. Latin and English lessons were taken by Guv, maths taught by Mr. Gibson, and French by a Miss Scott. Miss Reader, a fierce lady, armed with a ruler for knuckle rapping, taught piano.

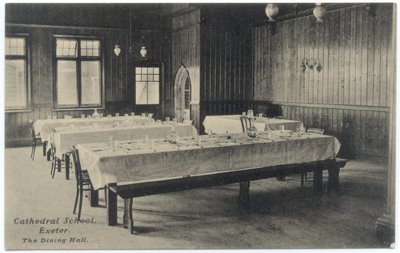

The Dining Hall as it was in 1912. Not quite the image described by Andrew! (from the archive of 1912 postcard photos)

Meals were served in a single storey dining room, which linked the main building to the Langhorne residence dining area. Uniformed and superior Maids serviced the family while the boys ate traditional boarding school fare such as hot pot, sultana suet pudding at lunch, and bread, margarine and jam for tea.

In front of the main school building was the tarmac playground used for soccer or cricket by season.

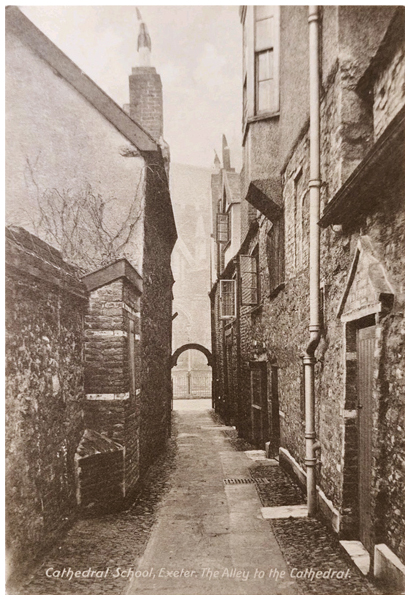

The alley as it was in 1912 (from the archive of 1912 postcard photos).

An alley to the south led to the Cathedral Close while another double door gate at the north end gave access to the town. Flannel suits and caps were worn on days off, with Eton suits, Eton collars and mortarboards for the twice-daily crocodile to and from the Cathedral.

The highlight of the summer term was Pa Pics party – a strawberry, cream and meringue event given by Mr. Pickard at Dellers restaurant. To my eternal shame, at my first of these events, when the host tapped me on the shoulders saying “what a handsome little boy!” I spewed everything over the table.

The pleasure of singing from chants to services and anthems, once installed as a full chorister, was truly wonderful. I will never forget my first solo, “Lead me Lord”, my later promotion to Decani’s corner boy and Head Chorister, and the privilege of singing “Hear My Prayer” and “The Wilderness” – each at least twice. To my regret, I was never given “Hodie Nobis” at the Christmas Eve service!

Being away from the family at Christmas and Easter was obviously painful, but we were compensated by presents and enormous eggs, and packed our trunks and tuck boxes for rail travel home a day or so later.

I am afraid there were some misdemeanours. The most serious involved upsetting the famous old Cathedral clock, while admiring the gas floodlighting in November 1933. I was the last of the choristers in the gallery of the North transept on our return from the tower when I saw an ascending and descending rope. I pulled it, and the tower bell struck nine times. Five minutes later, when we were in the Vestry, it struck ten. Needless to say I had to confess, and I got beaten. However, having breakfast at the Deanery one Sunday morning about a year later, Dean Carpenter told me that the clergy had been highly amused, and that I was forgiven.

My voice broke when I was 14 in 1937, and I left to take School Certs at Ilfracombe Grammar School. To his great credit, Guv wrote to me frequently, including during the War years, when I was abroad in the Fleet Air Arm, right up to his death. The whole experience was invaluable in giving me self confidence in my future career and a love of music which will be with me for as long as I live.

(Reprinted from the ECOCA Newsletter, February 2010)