| Exeter Cathedral Old Choristers' Association |

Stories and Anecdotes about the choir |

ECOCA > Stories | ||

Add your stories or comment on these - send to Mike Dobson

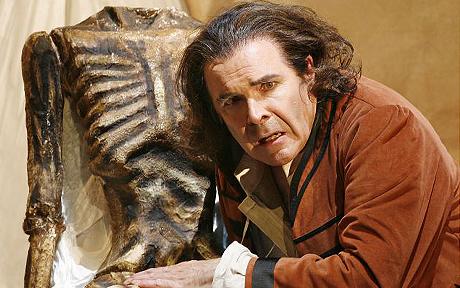

Richard Salter (treble 1952-57) (1943-2009) (photos: upper - Daily Telegraph; lower - The Times) "Richard Salter, who has died aged 65, was a founder member of The King's Singers, the celebrated a cappella group of choral scholars which emerged from King's College, Cambridge, in the mid-1960s; within a few years, however, he had been lost to the German-speaking world, carving out a reputation for delivering baritone roles in the most difficult of contemporary operas" (Daily Telegraph obituary, 23rd February 2009 - for full obituary see below) |

I was looking up Howard Treneer on Google because I have just been rereading his sister, Anne Treneer's splendid book School House In The Wind. I still look on Howard Treneer as having been a wonderful headmaster and a great humanitarian. I should like to know if any other old Exeter choristers would be interested in collecting anecdotes about him. The interpretation I received of 'Patron' and 'Matron' was actually a short form of Pa Treneer (sic Ma Treneer). In fact they were 'Patren' and 'Matren'- as in 'Cave, Patren!'. Masters were in my day usually called Pa, followed by their surname. Occasional deviations from this norm include the unfortunate next Headmaster but one, James Woodhouse, (also a wonderful man), who became 'Lousy' derived from 'Woodlouse' and thus 'Cave, Lousy!'. He did get wind of this nomenclature and, not understanding the actual basis he requested that he should also be called 'Patren'. Of course these names were only designed to be used behind the teachers' backs. Of course they KNEW ALL! Our beautiful piano teacher was called Pamela Mapledorum - what a name! Then she married and became known as Ma Ouseley; not quite the same thing I'd say. The boy in the glasses in the 1952 cricket photo was Stewart Douglas, a very fine treble and a very ham actor. Can any other old choristers remember his version of Shivering Shocks, or The Hiding Place performed in the chapter house in (probably) 1953. Does The Ghost of Bishop Marshall still haunt the chantry? This ghost terrified those not in the know but actually consisted of a sheet let down by seniors from the window above on a rope and a coat hanger, accompanied by as low voices as could be manufactured. This was designed of course to scare the living daylights out of us junior tics. Can anyone remember clandestine midnight feasts and the craze for crystal sets? We ALL had to have cold baths every morning and these were hard to avoid as the master in charge was obliged to come in and check we weren't faking. If possible we would get into the bathroom quickly and spread water over the floor but that didn't fool the masters and we would then have to go through it all properly under beedy (and sadistic?) eyes. It was, so to speak, shiver shiver, climb in, turn over, get out and dry. It did wake us up and without doubt turned us into true Spartans! It was followed by a brisk walk through the Bishop's Palace Gardens, round Calendarhay (?) and back to school, passing a sweet shop on our way back where (after 'rationing' was over (1953?) we bought 'illegal' sweets if we had any cash. Can any chorister remember 'Ferdy Swag'? This consisted of the munificence of one Ferdinand Langmaid, one of the Cathedral Ushers (?) who liked to treat us when he was on duty. The lucky recipient was usually a more senior boy who was setting out the choir books in preparation for the service, usually Sunday evensong. 'Ferdy Swag' was whatever he saw fit to hand over. I remember things like Maltesers, Rollo,etc. There was NEVER any suggestion that he had ulterior motives! The 'Angel Voice' from my time (1952-57) was that of Michael Hagyard. He was also an adult musician of some note, but died tragically young. His parents were very keen film photographers and I suspect that material from that period is still around and very much treasured. In Memoriam (1943-2009) Richard provided the anecdotes above by email to Mike Dobson in July 2008. Very sadly he died on 1st February 2009 from a stroke, aged 65. He very modestly said in his emails simply that he was an opera singer and had been singing in Germany since 1971. His obituaries in The Timesand the Daily Telegraph reveal a great and highly respected musician and are a very fitting tribute to a former chorister: The Times (February 10, 2009 )

Richard Salter: baritone and founder member of the King’s Singers Singers the world over are fortunate that Germany’s almost 80 opera companies recruit performers from everywhere. But British artists who migrate to Germany often disappear almost without trace as far as their native country is concerned. That was what happened to Richard Salter, who was the baritone of choice for contemporary opera throughout the German-speaking world. After years of taking the leads in new operas in Hamburg and Munich, Salter had been due to create the title role in Kepler, Philip Glass’s new opera about the 17th-century astronomer. Salter had only ever sung one operatic role in Britain: Chorebus in the highly successful Tim Albery staging for Opera North of Berlioz’s The Trojans in 1986. Richard Jeffery Salter was born in Hindhead, Surrey, in 1943, and was a choral scholar at King’s College, Cambridge, having been a chorister at Exeter Cathedral (1952-57) and then educated at Brighton College. He was one of the original King’s Singers, one of the most successful British male voice group of the past 40 years. But, as he wrote in their silver jubilee programme: “I have been singing in Germany for over 20 years . . . I would probably have been banished anyway as I don’t think I took it seriously enough.” He was extraordinarily modest, almost humble, about his success. But he was always a great joker. He, Simon Carrington, Brian Kay, Alastair Hume and the rest were discussing with Mike Bremner, of Decca, what to call themselves if they got a record deal. Bremner’s idea was the King’s Singers for serious music and the King’s Swingers for close harmony. Salter, mindful that Peter Pears had set up a similar group called the Wilbye Singers, suggested the Wontbe Singers. He wrote in that silver jubilee programme that his own style of performing was already too operatic and not precise enough, once concepts such as rhythm, precision, singing in tune and blending began to take over. “I could see the writing on the wall and began to look around for alternative sources of employment like doing contemporary music where one wouldn’t need to sing in tune.” When he left Cambridge in 1965, Salter worked as a session singer to pay for a couple of years at the Royal College of Music. He had already shown his fellow choral scholars at King’s that he was serious about technique. Al Hume remembers his voice then as not the smoothest or creamiest. Neither was it specially liked by David Willcocks, whose prime commitment was to the concept of “blend”. Salter was his own man with clear ideas of what singing was about. But criticism from Willcocks made him buckle down to the challenge of developing a cast-iron vocal technique. By the time he left (after reading English) he could, according to Carrington, tackle almost anything with confidence, limitless breath and astonishing stamina and flexibility. Salter kept in touch with his fellow King’s Singers with typically self-deprecating missives. A year ago he wrote about how difficult it was to retire: “In January I was asked to rescue a world premiere in Antwerp of an opera based on La Strada (not every day you get asked to imitate Anthony Quinn!). Anyway I decided to do it, truly terrifying but of course well paid. My goodness, memory! The next thing is Mark-Anthony Turnage’s Greek in Hanover starting next week, and finally in June a Barbican appearance with Philip Glass’s Waiting for the Barbarians which I ‘created’ in Erfurt, then did in Amsterdam and then last January in Austin, Texas. I am considering this to be my real swan song.” But in fact the work just kept coming. Salter died the day before he was due to start rehearsals at the Karlsruhe opera for the baritone lead in Britten’s Death in Venice and several other parts that he had never performed before. Waiting for the Barbarians at the Barbican earned him fine British notices as the Magistrate — not that those writing about him knew of his 37-year German career as a contracted member, most of that time, in operatic ensembles at Darmstadt, Kiel, Bremen and the Munich Gärtnerplatztheater where he was made Bayerischer Kammersänger in 1994. The King’s Singers first performed in May 1968 at the Queen Elizabeth Hall. Almost simultaneously Salter was awarded the Richard Tauber prize of the Anglo-Austrian Music Society and went off to Vienna to study at the Hochschule für Musik und darstellende Kunst. In 1971 in Darmstadt Salter began his German operatic career in which he performed with distinction virtually all the roles in the classical baritone repertoire — in faultless German, vernacular then being the rule as at English National Opera. Salter was brilliant at making atonal or modern music sound natural and acceptable. He was also a very quick student and superbly accurate. He played the title role in Wolfgang Rihm’s Jakob Lenz, and scored a series of successes in works such as Rihm’s Die Eroberung von Mexiko (also at Hamburg State Opera), Manfred Trojahn’s Enrico (for Schwetzingen), Aribert Reimann’s Das Schloss (in which he played K), and Jörg Widmann’s Das Gesicht im Spiegel (as Milton — both the latter were at the Munich Opera Festival). He was Hamlet in Rihm’s Die Hamletmaschine in Hamburg, The Master in York Höller’s The Master and Margarita in Cologne, and Coupeau in Kleber’s Gervaise Macquart in Düsseldorf. He also appeared as a guest at the Deutsche Oper Berlin, and in Brussels, Frankfurt, Paris and Vienna. He was especially proud of his Beckmesser, which he played memorably in 1988 at the Palais Garnier in a Meistersinger staged by Herbert Wernicke borrowed from Hamburg. He took the title roles in Falstaff and Gianni Schicchi. He shone as Pizarro, Germont, Wozzeck, Dr Schön in Lulu, Escamillo, Belcore, Malatesta, Silvio, Tonio, Marcello, Sharpless, Michele, Fra Melitone, Renato, Posa, Luna, Rigoletto, Miller, Onegin, Don Giovanni, Almaviva, Guglielmo, Don Alfonso, Papageno, Lindorf/Dappertutto, Figaro, Dandini, Alindoro, Musiklehrer, Kaspar, Ottokar, Beckmesser and Wolfram. He made his Carnegie Hall debut in New York in 1999 in Bernd Alois Zimmermann’s Requiem for a Young Poet. He was also a fine lieder singer — not least because of his flawless German. Salter is survived by his wife, Deirdre, and a son and two daughters. Richard Salter, baritone, was born on November 12, 1943. He died after a stroke on February 1, 2009, aged 65. source: http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/comment/obituaries/article5696257.ece accessed 14th July 2009 Daily Telegraph (23rd February 2009)

The King's Singers had their origins in a group of six students who, in 1965, made a recording of unaccompanied vocal music entitled Schola Cantorum Pro Musica Profana in Cantabridgiense. They were soon offering their services to friends and colleagues. As Alistair Hume, another of the original King's Singers, once wrote: "We carried on our undergraduate singing after university, contacted all our old schools and offered them a concert for the price of a pint of beer during the vacation in the summer of 1965." Engagements under the title "Six Choral Scholars of King's College, Cambridge" followed until a concert was arranged at the Queen Elizabeth Hall on May 1 1968, which forced them quickly to think of a more catchy name. The sextet's problem was that their repertoire was so wide-ranging that they could not be easily pigeon-holed or categorised. Having considered The King's Swingers as a name, they finally settled on The King's Singers. The group's first three years had been somewhat light-hearted. Now there were recording contracts, broadcasting opportunities and international touring possibilities. Although Salter sang in that first concert – as did the future broadcaster Brian Kay – his ambitions lay in opera. Asked why he left the King's Singers so swiftly, Salter (half-jokingly) replied that he found the increasing need for the group to scrub up and take themselves seriously to be off-putting: "I could already see the writing on the wall and began to look around for alternative sources of employment like doing contemporary music where one wouldn't need to sing in tune," he quipped. Richard Jeffrey Salter was born at Hindhead, Surrey, on November 12 1943 and, after a spell as a chorister at Exeter Cathedral and schooling at Brighton College, read English Literature at Cambridge, where he sang at King's under the direction of Sir David Willcocks. He took vocal lessons at the London College of Music, but winning the Richard Tauber prize gave him the opportunity to move to Vienna to further his studies. His mastery of the German language was complete, making him a natural choice both as a lieder singer and for the major opera houses at Darmstadt, Munich, Bremen and elsewhere. And while contemporary opera might have been his trademark – he appeared, for example, in new works by Manfred Trojahn and Wolfgang Rihm – he was equally at home as Sharpless in Madame Butterfly or Almaviva in The Marriage of Figaro. In 1999 he sang in the first American performance of Bernd Alois Zimmermann's haunting Requiem for a Young Poet at Carnegie Hall, New York, almost 30 years after the composer's suicide. Apart from a season in the Glyndebourne Chorus in the early 1970s, Salter's only post-King's Singers foray on to the British stage was in 1986, when he sang Coroebus in Berlioz's Trojans with Opera North. He kept in touch with the fortunes of The King's Singers, however, writing a moving tribute for their 25th anniversary programme in 1993. Four years ago he took the title role in Philip Glass's new opera Waiting for the Barbarians, based on the novel by the South African writer JM Coetzee about state-sponsored torture and repression. The opening night in Erfurt, in Germany, earned a 15-minute standing ovation, and when it crossed the Atlantic The New York Times declared that Salter – who was on stage for nearly the entire opera – "conveyed outrage and weary defiance in his riveting portrayal" of the Magistrate. In 1994 he was appointed Kammersinger, an honorary title, by the Bayerischer Staatsoper in recognition of his conribution to both German and contemporary opera. Richard Salter, who died in Karlsruhe on February 1, the day before he was due to begin rehearsals for Britten's Death in Venice, is survived by his wife, Deirdre, and by a son and two daughters. source: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/4788792/Richard-Salter.html accessed 14th July 2009 |